7 Tips to Make Indoor Riding Translate Outdoors

I became an indoor cycling instructor to maintain riding fitness during the increasingly brutal DC winters. I honestly did not intend to teach. When I take a class, I ride with purpose … with a plan in mind. I tend to sit in the back of the room and get into a zone. Apologies to my fellow instructors for not doing the choreography.

My cycling goals stretch beyond the number of classes I take each year. It's more like a recent ride I took along the coast of Portugal. Cycling in February does not get much better than this. But I had to put in work in December and January to have the confidence to attempt this ride.

Here are seven indoor cycling tips to prepare for riding outdoors:

1) Train Your Weakness

It’s important to know why you are riding and to ‘train your weakness.’ If you’re good at sprints, add more resistance and work on your sweet spot or steady-state intervals. If you love being out of the saddle, try staying in the saddle longer and focusing on cadence/form.

There are three main variables when riding an indoor bike: cadence, resistance, and time. The ability to increase your effort (cadence x resistance) and maintain power (watts) for longer durations is a healthy cycling goal. If you ride every song the same, you won’t see improvements.

2) Perfect Your Pedal Stroke

Endurance cycling is about finding the perfect marriage between cadence and resistance. Slight improvements in either pay dividends as you increase your distances. Finishing a four-hour ride 20 minutes faster is a worthy accomplishment!

Most cyclists pedal at a cadence between 80 and 100 rpms. Cyclists use their gears (think resistance) to adjust the amount of effort needed to turn the pedal based on terrain (hill or flat).

It’s pretty easy to coast through a spin class. The pedals are flying, sweat dripping, but your legs are simply following the pedals, not actually pushing them. You've not invited your leg muscles, via resistance, to join the 'cardio party.’ If you want to excel outside of spin class, finding resistance that forces your legs to exert force on the pedals consistently is essential.

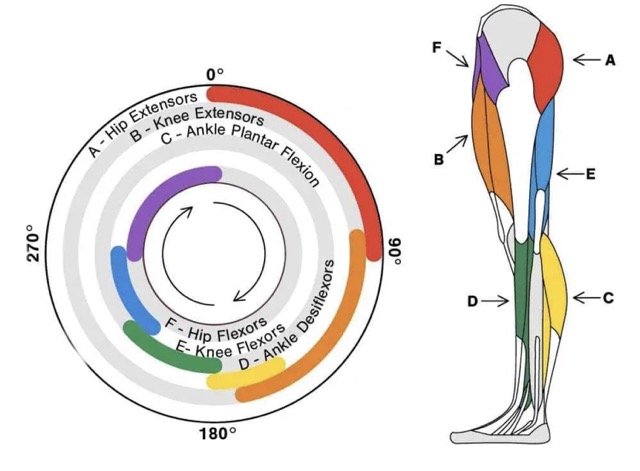

I like to think of my pedal stroke like a clock. I primarily focus on the range from 12 o'clock through 9 o'clock. 2 – 6 is the most powerful part of the stroke, with 2 to 8 becoming my prime range when climbing. On heavy efforts 6-10 can give you that added oooommmppphhh but will tax your hamstrings if you overdo it. As a rule of thumb, I always like to ‘feel’ 2-5. I know I am working when I feel that part of my stroke.

3) Don't be afraid to sit and spin

It doesn't matter if you are riding 25 miles or 125 miles; you will spend 90% of your time in the saddle. Studies show riding out of the saddle results in a breathing increase of about 10%, though effort and efficiency are essentially unchanged.

When riding outdoors, the penalty for excessive riding out of the saddle is premature fatigue. As you go up the hill, you run out of breath, and then you walk with your bike next to you. Indoors, most avoid shame by turning down the resistance. If we only had that option outdoors! Learning how to effectively use cadence to modulate effort (i.e. spinning) makes you a better rider.

4) Resist the Sway

Ok, so you REALLY want to get out of the saddle, FINE. Let's discuss how to work out of the saddle effectively. The biggest miscue is excessive sway...or the pendulum effect. You are out of the saddle, leaning left and right to push the pedals down. It looks cool when done to the beat, but it robs your legs of the workout.

The image below shows two of the world’s best cyclists out of the saddle. Though their bikes are leaning, their center of gravity remains directly over the crank. The swaying back and forth is reserved for the last part of the climb … after you’ve exhausted all recognizable semblance of a pedal stroke. As the right leg goes down, cyclists grip the left side of the handlebar to assist in pulling the opposite leg up. Their center of gravity remains vertical. Cuz, if not, they will fall. You don’t have to worry about that indoors

One of my favorite cues while out of the saddle is to “think of your legs as pistons,” pumping up and down. You want energy to go directly onto the pedals. The left and right motion adds little to the process. Don’t be the big kid on the see-saw. Let your legs do the work!

5) Light on the Handlebars

‘Light on the handlebars, like you’re playing the piano,’ is a reminder I give each class. Higher handlebars mean less stress on the lower back, and your weight is shifted forward, easing the core. Indoor riders often prefer this setup and the relief a more upright position offers. Riding outdoors, this position turns you into a sail — creating excessive wind resistance, thus slowing you down.

Setting your handlebars lower, in a position that mimics your bike setup, makes your workout more transferable outdoors. This may require some core work to feel comfortable, as a weak core is part of why folks come out of the saddle. The only way to stay light on the handlebars is to ask your core to hold you up. I usually run through the following checklist to check my form:

drop your shoulders

relax your forearms

remove the death grip from the handlebars

If done correctly, your weight will sink into the pedals, generating more force and producing higher watts. Anytime you lean on the handlebars, you reduce the intensity of the workout.

6) Push Yourself to Fatigue

Pushing yourself to exhaustion is critical to improving as a cyclist. One of my favorite cycling books is Time

Crunched Cyclist. It espouses using intervals as the fastest way to see gains on the bike. That means you push beyond your limit for a period of time, recover, and then do it again. You MUST earn the recovery.

So, take sprints seriously. Take out of the saddle surges seriously. Take recovery seriously. Training with a heart rate monitor is one way to gauge effort. Once you figure out your heart rate zones, you can use the feedback to measure effort. Many indoor bikes will pair your heart rate monitor and show your results on the display.

7) Experiment with different positions on the bike

If the goal is to become a better cyclist, don't be afraid to sit in a corner and sneak in some saddle time while everyone else is standing. I find many indoor riders stand to escape the discomfort of climbing in the saddle. Instead, experiment with alternate riding positions. When climbing, slide your hips forward on the saddle. The slight angle change provides more leverage on the downstroke — think of a hammer hitting a nail.

Alternatively, slide back in the saddle and emphasize your hamstrings on the downstroke, allowing your quads to recover. This position enhances your ability to pull up on the back pedal — engaging your glutes and hamstrings.

—

In closing, none of the above is necessary if becoming a better indoor cyclist is your primary goal. Until indoor cycling becomes an Olympic sport, this hardly seems worthwhile.

What are your outdoor goals? Let me know in the comments below.